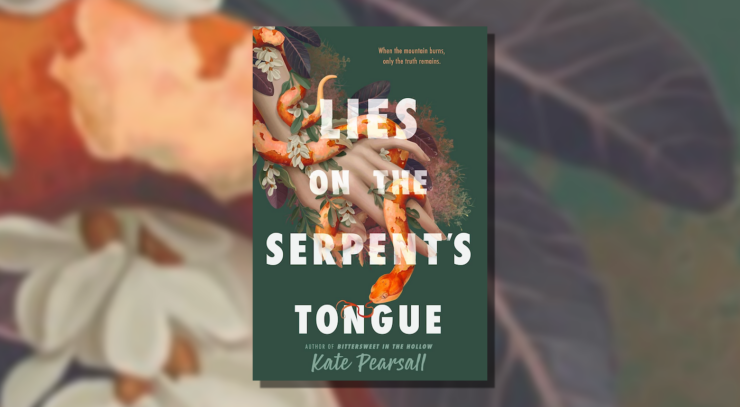

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from brand new YA fantasy novel Lies on the Serpent’s Tongue by Kate Pearsall, a companion to Bittersweet in the Hollow—out from G.P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers on January 7.

Everybody lies. And in knowing their lies, I become the keeper of their secrets.

As Caball Hollow slowly recovers from a tumultuous summer, the James family must also come to terms with their own newly revealed secrets.

18-year-old Rowan James has spent her whole life harboring unpleasant truths—that’s what happens when you can smell lies on the teller’s breath—and building walls around herself to block them out. Like her younger sister, Linden, who can taste the feelings of others, Rowan has long struggled with her gift, which has taught her that everyone distorts the truth, and no one is who they seem to be. So when her old rival Hadrian Fitch shows up on her front porch—bloodied and bruised and asking for the kind of help only she can provide—her first instinct is distrust.

Except Hadrian’s attack isn’t the only strange occurrence. Now small items are disappearing, but rather than report the losses the owners act as if their missing things never existed. Rumors of a new monster prowling the Hollow begin to swirl. But how can Rowan smoke out the culprit in a town full of secrets? And worse, how can Rowan trust beautiful, solemn Hadrian when every other word he speaks has the distinct burnt smell of a lie?

“What do you see in the tea leaves, Linden?” I ask. Maybe if I know what monsters haunt her dreams, I can help to slay them. But there are so many possibilities, from moths’ wings to river rapids, and I’m not sure where to begin.

Linden clears her throat before she blinks and looks down into the dregs of her cup. “It’s a person,” she says at last, her eyes wide and shining in the low light when she meets mine. “Falling, and falling, and falling.”

I watch her face as she seems to get lost in her thoughts for a moment, then gives herself a little shake, smiling gently when she realizes I’m staring.

“I’ll be all right,” she insists.

I brace for the foul scent of a lie, but it doesn’t come. And in the back of my mind, I’m still not sure if that means she’s telling the truth or my ability is failing me again.

“Let’s try to get some sleep.” She nods toward the stairs.

“We’ve only got a few more hours until morning chores.

* * *

I’m up before the sun, pulling my thick barn jacket tighter against the biting whisper of cold that tries to slide down the collar like a snake in a mouse burrow, seeking hidden warmth to steal away. There’s a promise of winter already in the air this early in the day, a crisp freshness beneath the acridity of burning leaves wafting from the next holler over.

I shut the kitchen door behind me, then tuck my hands up into my sleeves and away from the nibbling chill as I make my way to the coop to let out the chickens, too stubborn to break out my gloves in September no matter how cold it is.

Morning chores are among the worst on the farm and often include getting head-butted by impatient goats looking for breakfast, hunting down the eggs our bantam hens like to hide in the rafters, and shoveling shit out of animal pens. All of which should have been the responsibility of our farmhand, Hadrian Fitch, had he not taken off at the end of August, emptying his room over the carriage house without so much as a word and disappearing just as suddenly as he’d arrived the year before.

I warned Gran not to hire him. He showed up in his ripped jeans, untamable dark hair, with tattoos crawling up his neck, and a fiddle case under his arm. Then softened her up with some story about searching for his long-lost brother that wasn’t even a fraction of the whole truth. From first glance, I knew he was trouble.

I’m glad to have seen the back of him. Every single word that boy said was untrue. I’d rather clean the barn every day for the rest of my life than catch the lies that fall from his lips like ash.

A memory appears unbidden in my mind: Hadrian leaning against the counter just inside the kitchen, wild curls even darker in the shadows.

I was at the table, eating a breakfast of streaky bacon and fried eggs, focused on soaking up the runny yolks with a hunk of last night’s cornbread, when he came in.

Buy the Book

Lies on the Serpent’s Tongue

“You hungry, son?” Gran asked from the stove, where she was frying up more eggs in bacon grease, scooping a little over the top until they were perfectly cooked. “These are almost ready. Grab a seat.”

“I’ve got to see to the sheep first, ma’am,” Hadrian said. “But if it’s not too much of an inconvenience, I need to take the truck out to the feed store in Rawbone. We’re running low on hay pellets and wood shavings.”

The sharp scent of a struck match, sulfur and burning wood, hit me, and my head jerked up. But he wasn’t looking at Gran. His eyes were locked on me like a challenge.

“Well, that’s just fine,” Gran answered, turning her full attention back to the stove. “You know where to find the keys.”

I caught the tiny smirk before he grabbed the truck key from the hook by the door and headed back outside. I dropped my fork and pressed my hands against the table, the stench of the lie roiling my stomach and forcing me to my feet to follow after him.

He was nearly to the gate of the sheep pen when I stepped out onto the porch. The flower boxes were right there, and I didn’t even think before plunging in my hand and taking aim at the back of his head. The first dirt clod missed, sailing wide and nearly hitting Linden as she wheeled the old red bike out of the barn, but it got his attention. He spun around to face me.

“If you can’t be bothered to tell the truth, at least keep your stinking lies from spoiling my breakfast,” I yelled. More than anything, I wanted to sink my fingers back into the mud and knock the smug look off his face.

Hadrian lifted a single dark brow, a gleam in his mossy green eyes. “What are you on about now?” He feigned confusion.

“You told Gran you needed the truck today to go to the feed store.” I ground the words between my teeth, giving up any attempt at resistance and chucking another handful of soil at his head. This one only missed by inches, raining dirt into his hair.

I stalked down the steps toward him. “But you and I both know that’s not true. So where are you really going?”

“Rowan, stop.” Linden dropped the bike and grabbed my arm. “You know what Gran said,” she whispered, reminding me of the edict to stop accusing Hadrian of lying or suffer the consequences. Gran had long grown tired of our feud and told me in no uncertain terms that if I had time to distract him from his work, then I had time to take on more work of my own. And they were always the worst jobs, too, like cleaning out the chicken coop or the grease trap at the diner.

My blood still boils at the way Hadrian winked at me over Linden’s shoulder.

Then I shove the memory away, forcing my attention back to the here and now. The sky is just beginning to lighten, the outline of the rolling mountains surrounding Bittersweet Farm sharpening into focus, as I walk the fence line, checking for damage. A weak fence is an open invitation to predators, but ours is woven through with the protective bittersweet vines that give the farm its name. Some claim it rose from the earth of its own accord. Though the first known James ancestor, Caorunn, was said to have a special talent for coaxing just about anything to grow.

I spot a frill of orange on the trunk of an old oak near the edge of the pasture and venture closer to investigate. It’s a cluster of chicken of the woods mushrooms, Laetiporus sulphureus, still fresh. Tender and bright. I flip open the small blade of the foraging knife I keep in my pocket and cut away several of the ruffled shelves it formed. It typically grows on dead or dying oaks, though not always, so I make a note to keep an eye on this one, before it can cause any trouble with the fence.

When I make my way back to the house, I pull off my muck boots on the porch and open the back door. The air smells like Gran’s famous cathead biscuits, and the heat of the oven has chased the early autumn bite from the air. Mama and Gran sit at the table, a pot of coffee between them.

“You out there doin’ all the chores alone again?” Gran asks as she blows over the top of her mug. “Your sisters are meant to help.”

“School starts early enough, let them sleep in a bit,” I say, dropping my bounty of mushrooms on the counter as I make my way to the sink to wash up. I’m the only one who doesn’t have to worry about getting to class on time anymore or staying up late to do homework.

Mama glances up at me as she surreptitiously rubs her thumb across something shiny, then tucks it back into her pocket. The shadows under her eyes look darker in the glare of the overhead light. Linden isn’t the only one who isn’t sleeping. I pretend not to see the small circle of the pendant, like I always do. She stopped wearing it after she and Daddy split, but she still carries it with her, reaching for it like a talisman when she thinks no one is watching. I’m not sure if it’s love or regret that haunts her.

The story goes that Daddy gave Mama the necklace on their first date. By then, he’d already eaten lunch at the Harvest Moon every single day for a month, trying to work up the courage to ask her out. Until one day, when Mama asked him if he was ever going to. He told her he’d found the necklace at a thrift store for a couple bucks and the swan engraved on the front made him think of her. In truth, he’d been saving a sizeable chunk of his meager pay since the day he met her to buy it from an antiques jeweler up in Charleston. It took a few months for her to realize the pendant was a locket with a hidden catch. When she finally opened it, a piece of paper with the words I’m already in love with you scrawled across tumbled out, and by that point, she felt the same way.

They’d been together ever since, until last year, when Mama traded their love to save Linden’s life.

I grab a golden biscuit from the pan and try to pull it apart without burning myself or getting scalded on the steam that escapes. After dropping both halves into a bowl, I smother their soft middles with a scoop of thick, peppery sausage gravy from the cast iron skillet on the stove.

“You should eat something, too, Odette,” Gran murmurs across the table.

“I will,” Mama promises. It’s not really a lie, but it’s clear she doesn’t mean anytime soon.

Gran and I exchange a look over her head. The loss of appetite, I suspect, is the guilt eating away at her. She hasn’t said as much, but I know she blames herself for keeping the secrets that put Linden in danger when all she’d wanted to do was to protect her.

“I don’t have to tell you”—Gran starts, settling back into the old wooden chair with both hands wrapped around her mug—“how I blamed myself when my sister took off. Zephyrine was so young when your granny Sudie passed, I think I took to mothering her whether she wanted it or not. I knew something was wrong toward the end. She looked plumb exhausted, and she was barely eating, but she’d already stopped talking to me on account of all my meddling. After she left, I let my own guilt stop me from going after her. When I think of all the time I wasted when I could have been looking for her.” Gran pauses, shaking her head.

Decades ago, she and her sister had a falling-out, ostensibly because Gran didn’t approve of the man Zephyrine was dating, but the real issue went deeper than that, to differences in how they thought we should use our gifts and our knowledge. Zephyrine trusted the man who she thought loved her with her secrets, and he used them against her. He used her to save himself, like a sacrifice to an old god he didn’t understand, though maybe a deal with the devil would be more apropos.

“I might have found out a lot sooner that she didn’t leave of her own accord. Sitting around stewing in your own juices don’t do no good for nobody. You need to decide what you’re gonna do about it.”

Gran pushes out of her chair and makes her way around the table. “I know what that kind of guilt feels like, but I’m not just going to sit by this time. Accept it or change it. Those are the only choices. Now that I know where she is, I’m going to do everything in my power to get her back.” She pats Mama’s shoulder as she moves toward the stove. “So, if biscuits and gravy aren’t to your liking, let me fix you up something else.”

I slide into Gran’s empty chair, and Mama meets my gaze across the table.

“You look so much like your father.” Her smile is a heavy thing, weighted with equal parts joy and sadness. Her words aren’t strictly true, either. My ink-dark hair and bright blue eyes are James family traits, but she searches out the pieces of him in each of us. His freckles on Sorrel’s skin, the exact shape of Linden’s smile, the curve of Juniper’s jaw, the set of my eyes. They can never quite add up to the whole, no matter how hard she looks.

“Did I ever tell you that I used to sit with him whenever I had a free minute during my shift? And sometimes when I didn’t,” she admits, lifting her eyebrows. “He listened like every word I spoke was a revelation. We created a whole world, he and I, one that existed only for the two of us. I would never take back the deal I made to save your sister, but I know why the Moth-Winged Man accepted the trade. A life for a life. I killed something that day. Something I can never get back.”

I stare into the deep blue of her eyes and realize it’s not the regret or the guilt that keeps her up at night. It’s grief.

“Your gran has hope now of finding Zephyrine. But I have to abide by my bargain. We don’t always get to keep what’s most precious. Sometimes we have to let it go.” Mama squeezes my hand, then leaves the kitchen while Gran is busy at the stove.

Zephyrine loved the wrong man, and it cost her dearly. Mama loved the right man and still lost. Their stories might be vastly different, but the end result was still the same. We don’t talk about our abilities. As many folks make their way down the garden path to the summer kitchen late at night, careful not to wake wagging tongues as they seek out cures for what ails them, none of them really want to know the truth. It’s one thing to believe there might be more to the world than what’s known, yet quite another to have it confirmed. People turn dangerous when confronted with something that challenges their worldview. Scorch marks mar the old log cabin wall from where long ago some disgruntled customer decided the best way to deal with a witch was the old-fashioned one. There’s a reason we don’t trust easy. It’s a lesson we’ve learned well enough over the generations.

Excerpted from Lies on the Serpent’s Tongue, copyright © 2024 by Kate Pearsall.